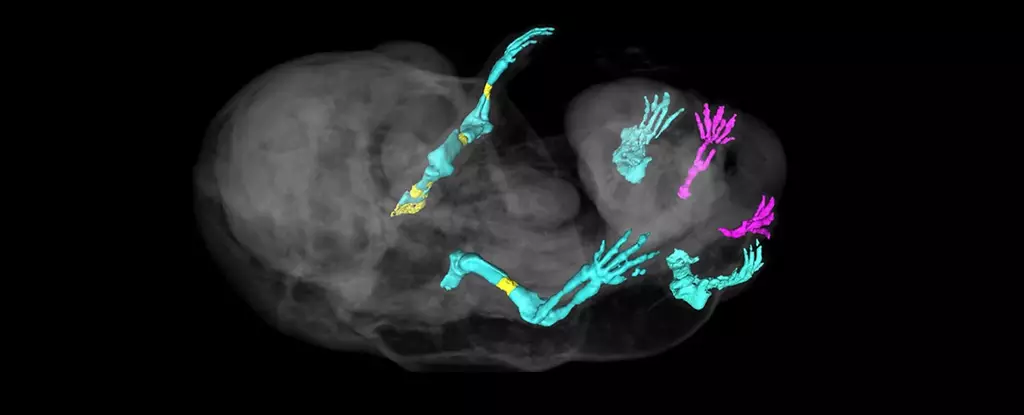

The accidental discovery of a six-legged embryonic mouse has sparked a new direction in spinal cord research for developmental biologists Anastasiia Lozovska and Moisés Mallo. The unexpected result occurred when a gene, Tgfbr1, was turned off early in mouse development, causing a mutation that resulted in the formation of an extra pair of legs. This strange outcome has prompted the research team at Portugal’s Gulbenkian Science Institute to delve deeper into the genetic mechanisms that govern embryonic development.

Tgfbr1 is a gene that codes for the Tgfbr1 receptor protein, which is involved in a signaling pathway responsible for providing trunk-to-tail directions during the development of a forming body. This pathway plays a crucial role in instructing the developing embryo’s cells to create hindlimbs or external genitals. As the mammalian embryo grows, it sequentially builds structures from head to tail, with genetic mechanisms shifting focus from the head to extend the body and lay the foundation for major organ systems. The activation of genes in multiple layers of tissue later extends the trunk to create a tail, generating structures necessary for the body’s exit channels and genitalia.

While legs and arms share many genes, hindlimbs and genitals have more in common early in the development process. It has been suggested that these structures may arise from the same initial primordium structure in ancestral species. The researchers are intrigued by the potential implications of their findings on the absence of hindlimbs in snakes and their presence in most lizards. Understanding the developmental plasticity uncovered by their work could shed light on these evolutionary differences.

Upon closer examination of the mutant leg tissue, the research team found that chromatin remodeling had occurred. This process involves proteins that control access to the cells’ DNA, which had been switched to a ‘legs’ configuration instead of a ‘genital’ configuration. The abnormal placement of the extra legs in the mutant embryos indicates that despite the structural differences, the genes expressed in these extra limbs are similar to those found in normal mouse limbs. The researchers suspect that as the limb cells push out into the surrounding tissue layers, they receive signals to develop into malformed but functional limb structures.

The discovery of an accidental six-legged mouse embryo has opened up new avenues for understanding the genetic and molecular processes that govern embryonic development. By unraveling the mechanisms behind the suppression of the Tgfbr1 gene and its impact on limb formation, researchers hope to gain valuable insights into developmental challenges and diseases. Further studies are needed to determine the exact mechanism by which the mutation leads to the development of an extra pair of legs, paving the way for the development of potential therapies and interventions for developmental disorders.

Leave a Reply