The recent commitment by China to reach carbon neutrality by 2060 has been met with enthusiasm by environmentalists. However, new research indicates that the decarbonization process may come with hidden costs and difficult environmental choices. The decarbonization of the China Southern Power Grid, which services over 300 million people, is expected to negatively impact river basins that run from China into downstream countries. Stefano Galelli, an associate professor in the School of Civil and Environmental Engineering at Cornell Engineering, emphasizes that every major technological change comes with costs and unintended consequences that need to be addressed to ensure a sustainable and equitable energy transition.

In order to achieve carbon neutrality by 2060, China would need to build several dams for hydropower production and convert a significant amount of cropland to support the growth of solar and wind energy. While technically feasible, this process would have significant ecological impacts, especially on transboundary rivers shared by multiple countries. Galelli highlights that the alteration of river flow due to new dams can have detrimental effects on riverine ecosystems and the communities that depend on them.

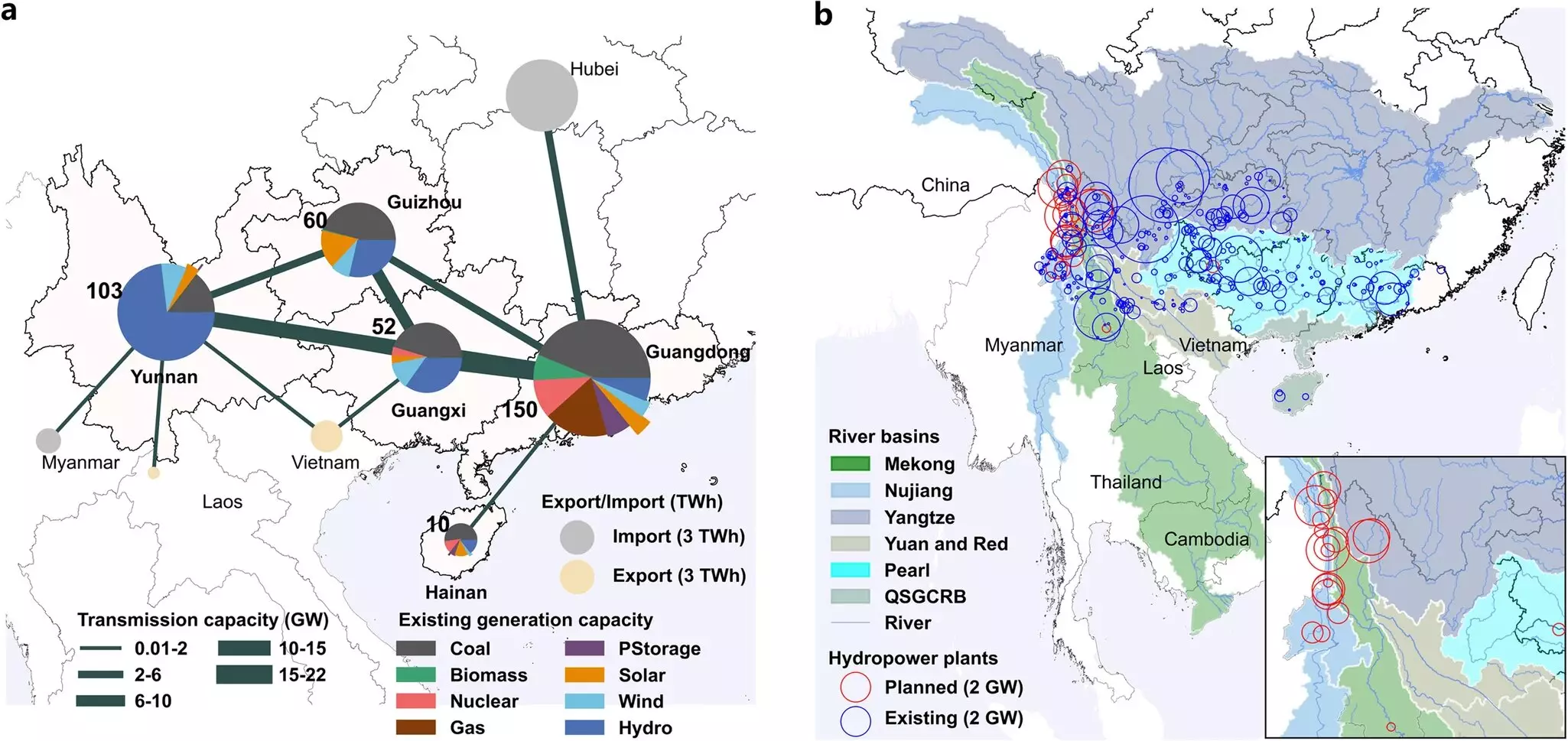

The impacts of decarbonizing the China Southern Power Grid would be particularly felt in major transboundary river basins such as the Salween and Mekong. These basins are known for their biodiversity and play a crucial role in supporting ecosystems and local communities. The construction of additional dams on these rivers could disrupt the flow of sediments and nutrients, impacting the productivity of ecosystems and fisheries downstream. This poses a threat to countries like Cambodia, where inland fisheries are a vital source of protein for the population.

Moreover, the implications of building more dams on the Mekong River and its tributaries must be carefully considered. The blocking of sediments and nutrients by dams can lead to a reduction in river delta productivity and exacerbate saline intrusion. Additionally, migratory fish species could be negatively affected by the alteration of river flow caused by dam construction. Galelli emphasizes the importance of accounting for these ecological impacts when planning large-scale decarbonization efforts.

The decarbonization of China would also entail ecological and sociological trade-offs in terms of land use. As China aims to increase food security and reduce reliance on imports, the conversion of cropland to support renewable energy projects could pose challenges. With the rapid growth of the electric vehicle industry in China, the demand for electricity is expected to rise, necessitating the expansion of renewable energy sources like solar and wind power.

However, building enough solar and wind plants to replace conventional coal power plants would require a significant amount of land. This could result in competition for land use, with certain regions bearing a disproportionate burden of renewable energy infrastructure. Galelli’s research indicates that Guangxi province, where crops and grasslands make up the majority of the land, would likely face significant ecological, social, and financial costs from the construction of solar and wind plants.

Overall, the journey towards decarbonization in China presents numerous challenges and trade-offs that need to be carefully navigated to ensure a sustainable and equitable transition to renewable energy sources. By considering the environmental implications and making strategic choices, China can lead the way in addressing climate change and transitioning towards a greener future.

Leave a Reply