When faced with a cardiac arrest, time is of the essence. A person whose heart has abruptly ceased to function may have mere minutes before the situation becomes irretrievable. In these critical moments, performing cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) can significantly enhance the chances of survival. CPR maintains blood circulation and provides essential oxygen to vital organs such as the brain until medical professionals can take over. Despite its importance, recent studies reveal a concerning trend: bystanders are less likely to perform CPR on women than on men.

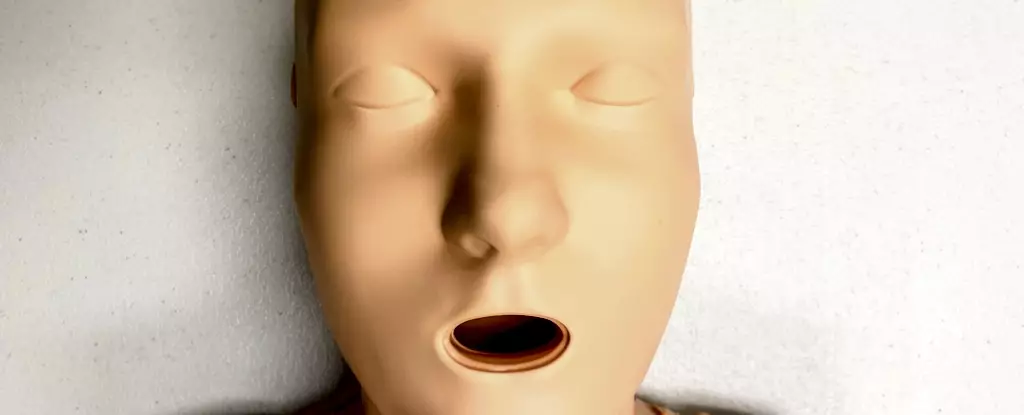

An eye-opening Australian study analyzed a staggering 4,491 cases of cardiac arrest from 2017 to 2019, discovering that 74% of men received CPR from bystanders, compared to only 65% of women. This disparity raises questions about the reasons behind it. One possible explanation could lie in the design of training manikins used around the world. Astonishingly, a recent investigation into CPR training manikins revealed that approximately 95% of them are flat-chested, a feature that may inadvertently shape perceptions of who is deemed worthy of intervention during emergencies.

While it is important to note that anatomical differences—such as the presence of breasts—do not affect the technical execution of CPR, these physical characteristics may influence the willingness of bystanders to act. Such hesitation, particularly when seconds can mean the difference between life and death, highlights a significant barrier in emergency response fueled by social and cultural factors.

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) represent a leading cause of mortality among women globally, including conditions like heart disease, stroke, and cardiac arrest. Alarmingly, women experiencing cardiac arrest outside of a clinical setting have a 10% lower likelihood of receiving CPR relative to men. Additionally, studies show that women not only face diminished chances of survival but are also at a greater risk of lasting neurological damage post-resuscitation. This troubling trend underscores a pattern of unequal health outcomes not only for women but also for transgender and non-binary individuals, who often face marginalization in medical contexts.

A 2022 analysis of CPR training manikins across the Americas further emphasized the lack of diversity in training materials, with an overwhelming majority being white and male. Such a disproportionate focus not only neglects the realities of gender differences in health outcomes but also fails to cultivate an environment where every individual, irrespective of gender identity, feels supported and capable of intervening in emergencies.

The reluctance to engage in CPR for women can be traced back to a range of sociocultural concerns. Bystanders might fear being accused of inappropriate conduct, worry about inadvertently causing harm, particularly due to preconceived notions of women’s physical fragility, or experience discomfort over the idea of touching a woman’s chest. This hesitation can be compounded by challenges in recognizing a cardiac arrest in women, as demonstrated by research that suggests onlookers are less motivated to expose a woman’s chest to initiate resuscitation. Even in gaming simulations that do not require physical contact, the disparity in response remains evident.

Training resources have not kept pace with the imperative need for inclusivity and gender diversity. A predominantly male-focused training environment fails to adequately equip individuals to respond effectively in real-life emergencies. Given that the behaviors learned in training are likely to influence actual responses during a crisis, it is essential to cultivate an understanding that encompasses all genders and body types.

The CPR technique itself remains unchanged regardless of whether an individual has breasts. What demands urgent attention are the cultural misconceptions tied to these differences. To counteract biases and encourage immediate responsiveness, CPR training must move toward a more inclusive model that reflects the diversity of the population in question. This means advocating not only for manikins that represent various body types, including those with breasts but also for increased education regarding the specific health risks women face concerning cardiovascular diseases.

When performing CPR, individuals should be reassured that essential actions can be undertaken without unnecessary delays. The correct method includes positioning the heel of one hand in the center of the chest and ensuring a firm, rhythmic compression. Notably, the task of removing a woman’s bra is not obligatory for performing CPR, however, caution is warranted if using a defibrillator, as certain clothing can interfere with its effectiveness.

The current state of CPR training and response exhibits disturbing inequalities that must be addressed. To ensure equitable outcomes in life-threatening situations, training programs should prioritize diversity and inclusivity. With adequate preparation and knowledge, bystanders can save lives without fear or hesitation, transforming the landscape of emergency response for all genders. A comprehensive reevaluation of training methods, combined with a societal shift towards understanding and addressing gender disparities in health, holds the key to fostering a proactive and compassionate approach to CPR.

Leave a Reply