The evolution of Earth’s continents over billions of years has fundamentally influenced the development of life on our planet. However, the mechanisms behind the formation of these land masses remain the subject of intense scientific debate. Central to this discourse is the question of whether ancient geological processes continue to operate today and how they relate to contemporary geological phenomena.

In a significant development, recent research led by David Hernández Uribe from the University of Illinois Chicago introduces critical new insights into this age-old debate. Published in Nature Geoscience, his paper calls into question the prevailing theory regarding the formation of continents, particularly the role of subduction—a process in which tectonic plates collide and push crust upward. Subduction, which is still active today, is often cited as the primary mechanism for the formation of the earliest continental crust.

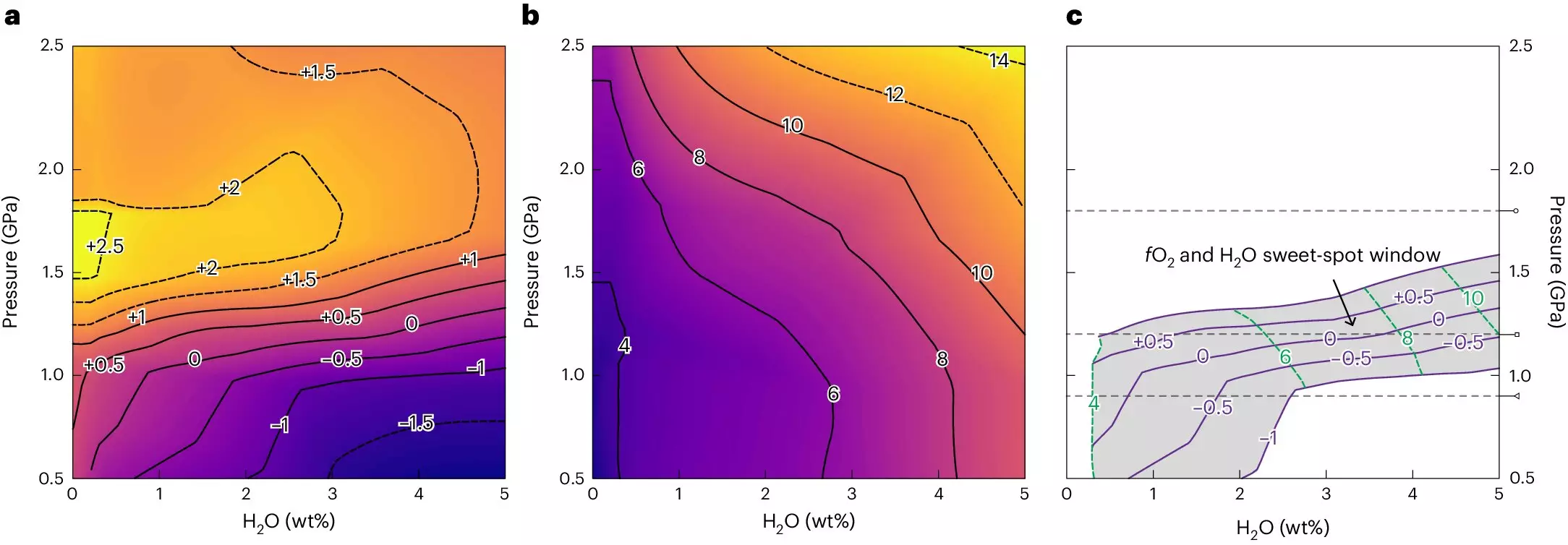

However, Hernández Uribe’s findings suggest a different narrative. By employing advanced computer modeling to analyze the origins of magma, the molten rock that solidifies to create the crust, he hints at alternative processes that could produce zircons—rare minerals that serve as critical timestamps in Earth’s history. His research points to the idea that rather than being solely a product of subduction, these ancient zircons might also emerge from high-pressure melting associated with the early crust’s formation.

Zircons, dating back to the Archean period (approximately 2.5 to 4 billion years ago), have long been utilized by scientists to gain insights into the early Earth. Previous studies, including a collaborative effort by researchers from China and Australia, proposed that these ancient zircons could only form via the subduction process. Yet, Hernández Uribe’s work indicates that the same zircon signatures could arise from partial melting at the bottom of the primordial crust, providing a more nuanced understanding of the geological events that predate the established timeline of plate tectonics.

Hernández Uribe candidly states, “Using my calculations and models, you can get the same signatures for zircons and even provide a better match through the partial melting of the bottom of the crust.” This assertion not only undermines the subduction-centric view but also introduces critical uncertainty about when tectonic activity began on Earth.

If the first continents emerged from processes associated with crustal melting rather than subduction, it suggests a considerably delayed onset of plate tectonics. This would imply that our planet’s geological dynamics evolved more gradually than previously thought. The potential delay in the initiation of subduction and plate tectonics raises fascinating questions about Earth’s geological timeline and the conditions necessary for sustaining life.

Hernández Uribe emphasizes the uniqueness of Earth in the context of the solar system, noting, “Our planet is the only planet in the solar system that has active plate tectonics as we know it.” With his research, he contributes to a growing body of evidence suggesting that Earth’s rich geological history is far more complex than current models can fully explain.

As science continues to unravel the mysteries of our planet’s past, research such as Hernández Uribe’s serves to challenge established paradigms and fuel further inquiry into the intricate processes that shaped—and continue to shape—Earth as we know it today. The debate surrounding continental formation is far from settled, and as new data emerges, it invites scientists to rethink and refine their understanding of geological history and its implications for life on Earth.

Leave a Reply