Anorexia nervosa is a complex disorder that affects a significant number of individuals, predominantly women. Characterized by extreme restrictions in food intake, an overwhelming fear of weight gain, and profound distortions in body image, anorexia can lead to dire health consequences, including severe anxiety, depression, and malnutrition. Recently, emerging research has begun to uncover the neurological underpinnings of this daunting condition, suggesting that alterations in brain chemistry may contribute to its development and persistence.

Understanding anorexia nervosa through the lens of neuroscience has become a crucial area of interest for researchers. A pivotal study has proposed that changes in neurotransmitter function within the brain may play a critical role in the onset of anorexia. Though the exact mechanisms remain elusive, insights from this research could potentially reshape treatment strategies and improve therapeutic outcomes for individuals suffering from this disorder.

Researchers have previously established a connection between anorexia and notable structural changes in the brain. Noteworthy findings from animal studies revealed that mice lacking the neurotransmitter acetylcholine in the striatum—an area integral to motor functions and reward processing—displayed behaviors analogous to human anorexia. This correlation between neurotransmitter levels and eating behaviors underscores the importance of understanding the biological bases of anorexia.

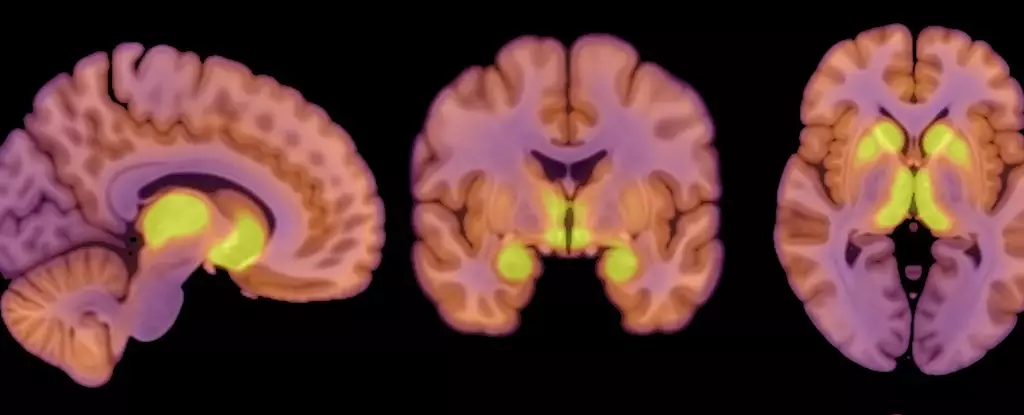

A significant component of this recent study is its focus on mu-opioid receptors (MORs), a subtype of protein receptors found throughout the central nervous system, which plays a role in regulating both food intake and the pleasure derived from eating. The study reveals that individuals with anorexia nervosa exhibit increased MOR availability in regions of the brain that are involved in reward processing. This increase in opioid neuromodulation may be one of the driving forces behind the altered appetite regulation observed in anorexia patients.

Co-author Pirjo Nuutila, a physiologist at the University of Turku in Finland, emphasized the contrasting dynamics of opioid neurotransmission in the context of anorexia versus obesity. While individuals with anorexia experience heightened activity of their opioidergic system, those with obesity tend to show decreased activity. This discovery adds a layer of complexity to our understanding of appetite and body image issues, suggesting that the body’s inherent reward systems may play a dual role in both cases, influencing behaviors that lead to either restriction or overeating.

The study monitored 13 women diagnosed with anorexia nervosa, comparing their neurological responses to a control group of 13 healthy women. The research aimed to measure the availability of MORs through positron emission tomography (PET) scans, while also examining how brain glucose uptake was affected by the caloric restrictions experienced by patients. Notably, this research showed that the brains of anorexia patients utilize glucose at similar rates as their healthy counterparts, despite the body’s overall reduced energy intake—indicating that the brain’s energy demand takes precedence even under caloric deficit conditions.

This finding illuminates how the brain strives to maintain its functionality amidst physiological adversities associated with malnutrition. Lauri Nummenmaa, a cognitive neuroscience professor involved in the study, reiterated this point by affirming that the brain maintains its glucose requirement to sustain critical functions, even if the body itself is starved for energy.

While the connection between MOR availability and anorexia nervosa is compelling, this study also has several limitations. The all-female sample raises questions about the applicability of these findings to male populations, as anorexia nervosa predominantly affects women. Moreover, the small sample size may limit the generalizability of the results. Researchers refrained from collecting subjective data on eating behaviors, recognizing that individuals with anorexia could react adversely to such inquiries, thus missing the opportunity to draw direct correlations between neurochemical changes and specific eating habits.

Despite these limitations, the research opens avenues for further exploration into the neurobiological components of anorexia nervosa. Understanding whether the alterations in opioid systems are a cause or an effect of anorexia remains a critical question that future studies must address. As the field of neuroscience continues to evolve, it is essential to consider the intricate balance between cognitive processes, biologic imperatives, and psychological influences at play in eating disorders.

Anorexia nervosa is a multifaceted disorder deeply rooted in physical, psychological, and neurological factors. The recent findings regarding neurotransmitter function and the role of receptors in regulating appetite may offer new perspectives on treatment strategies. As researchers delve deeper into the intricacies of this disorder, understanding the interplay between brain chemistry and eating behaviors could pave the way for more effective interventions, ultimately improving recovery outcomes for those affected by anorexia nervosa.

Leave a Reply