Bacteria are often regarded with trepidation, associated predominantly with disease and decay. Yet, beneath this unflattering veneer lies an extraordinary potential for sustainability and innovation. These microscopic organisms possess the capability to produce valuable substances such as cellulose, silk, and various minerals — materials that human civilization relies on. Bacterial synthesis of natural products is inherently sustainable, operating under mild conditions, including room temperature and aqueous environments. However, despite these advantages, the limitations in speed and scale have long hampered their industrial applicability. Traditional methods yielded small quantities, insufficient for meeting the demands of modern industry.

The quest to convert bacteria into efficient “living factories” has motivated researchers for years. This endeavor aims to harness the prowess of microbes to generate greater volumes of desired products more swiftly. Fundamental to this transformation is an understanding of genetic modification and strain optimization, crucial steps towards realizing the vision of enhanced bacterial production.

A Breakthrough in Bacterial Engineering

Recent research led by Professor André Studart at ETH Zurich has taken a significant plunge into this microbial realm, focusing on Komagataeibacter sucrofermentans, a bacterium renowned for its cellulose-producing abilities. This study aligns seamlessly with the principles of evolutionary biology, utilizing natural selection to engender a plethora of bacterial variants. By fostering an environment where tens of thousands of variants could thrive, the researchers aimed to identify strains that excelled in cellulose production, thereby addressing an urgent demand in various sectors, including biomedicine and sustainable packaging.

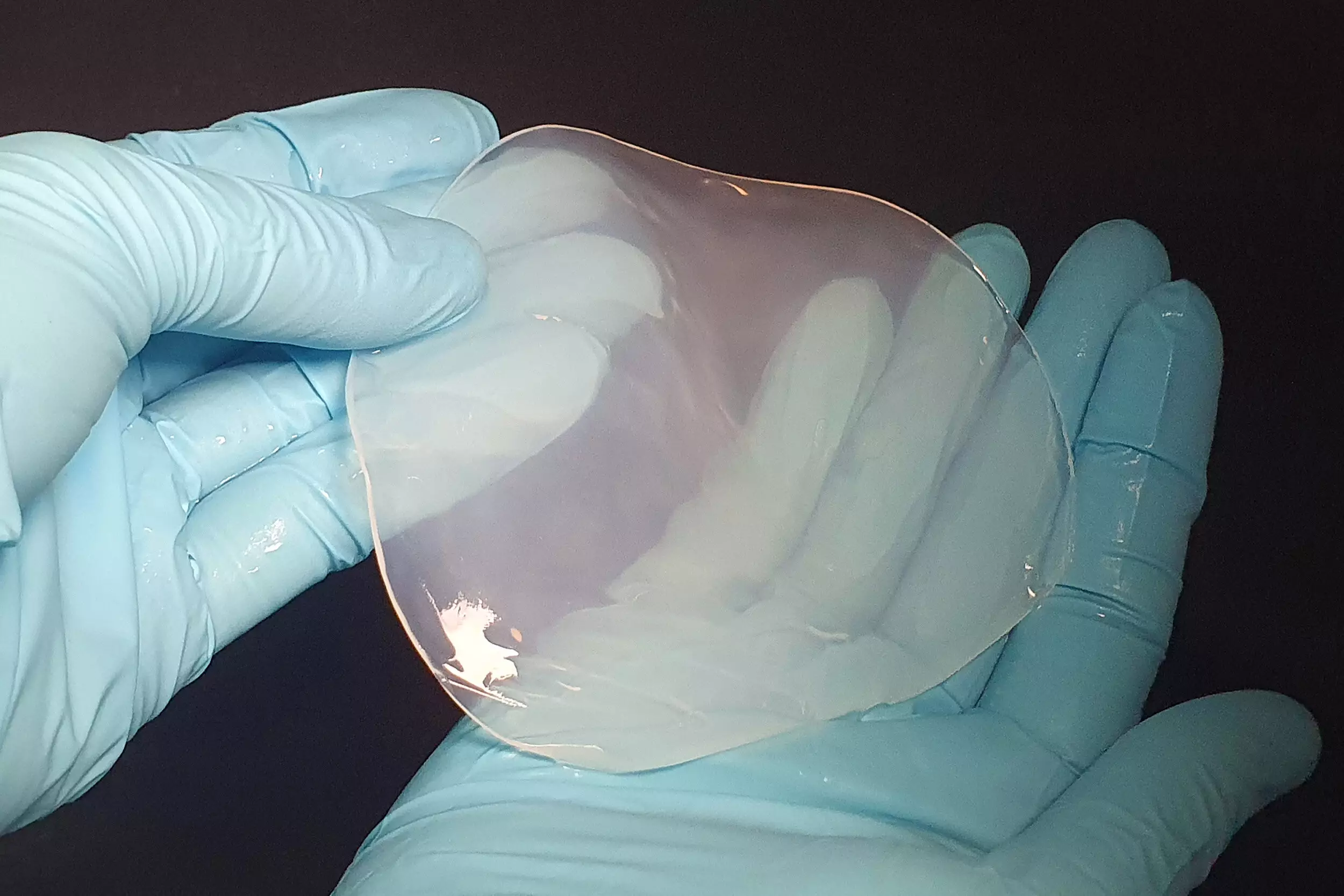

Cellulose, a non-toxic and biocompatible material, has notable applications in wound healing and infection prevention. However, the natural proclivity of K. sucrofermentans to produce significant amounts of cellulose is stumped by its slow growth rate. This limitation necessitated innovative strategies to optimize yields — a journey that Julie Laurent, a dedicated doctoral student in Studart’s cohort, adeptly embarked upon.

Evolving Bacterial Efficiency through UV Irradiation

Laurent’s pursuit of K. sucrofermentans evolution included a striking approach: exposing the bacterial cells to UV-C light. This exposure aimed to induce mutations by damaging random DNA locations, effectively creating a unique library of variants. The next step involved isolating these mutated cells in a nutrient-rich environment, where they could produce cellulose under carefully monitored conditions.

This is where the marvel of technology comes into play. Employing a sophisticated sorting system designed by chemist Andrew De Mello, Laurent’s team leaned into automation. In mere minutes, their system could evaluate half a million droplets — each containing a bacterial variant — spotting those cells which produced higher cellulose yields with laser precision. This efficiency allowed the researchers to zero in on just four variants demonstrating an impressive 50 to 70 percent increase in cellulose production compared to their wild-type predecessors.

The Genetic Secrets of Enhanced Production

A closer look at these prolific variants revealed a common genetic alteration, specifically in a gene coding for a protease — a protein-degrading enzyme. Surprisingly, the genes directly responsible for cellulose synthesis showed no modifications. The implication is fascinating: the presence of the altered protease likely compromises the regulatory mechanisms that govern cellulose production, essentially unleashing the cells’ potential to produce exponentially more cellulose without the normal control mechanisms halting the process.

André Studart champions this novel approach, lauding it as a milestone in bacterial research. This venture is not merely an isolated experiment; it taps into a versatile methodology applicable to other materials beyond cellulose,263 referencing the origins of such techniques geared toward protein generation.

Industrial Applications on the Horizon

With a patent filed for this groundbreaking method and the newly mutated variants, the next step is clear: collaboration with industrial partners who are steeped in the production of bacterial cellulose. The relevance of K. sucrofermentans extends beyond academic intrigue; it portends a future where industries can rely on microbial systems that are sustainable, efficient, and attuned to the ecological principles we must embrace moving forward.

As we stand on the precipice of this innovative frontier, the implications for the environment, healthcare, and sustainable materials are profound. The work of Studart’s team represents a paradigm shift in how we can leverage nature’s constructs to meet humanity’s burgeoning needs, unearthing the powerful potential hidden in the smallest of life forms. The microbial factories of tomorrow are quietly evolving, ready to reshape industries, foster sustainability, and inspire a new generation of biotechnological advancements. The future is bright, and it’s microbial.

Leave a Reply