Recent research by experts from iDiv, Leipzig University, and Sun Yat-sen University has underscored a pressing environmental concern: the effects of large-scale deforestation extend far beyond the immediate release of carbon dioxide. This new analysis reveals that deforestation may significantly contribute to global warming by reducing cloud cover, which is a crucial component of the Earth’s climate regulation. The findings challenge long-standing views on the interplay between deforestation and climate change, emphasizing the need for an updated understanding of ecological and meteorological interactions.

Traditionally, the warming consequences of deforestation have been attributed primarily to the release of carbon stored in trees. However, this study highlights a crucial, often overlooked, aspect: forests typically outperform cleared lands in their ability to reflect sunlight due to their darker surfaces. This unique property exerts a cooling effect that can mitigate some of the warming resulting from greenhouse gas emissions. Yet, researchers have discovered that the diminishment of cloud cover in deforested regions significantly diminishes this cooling effect, nearly halving it.

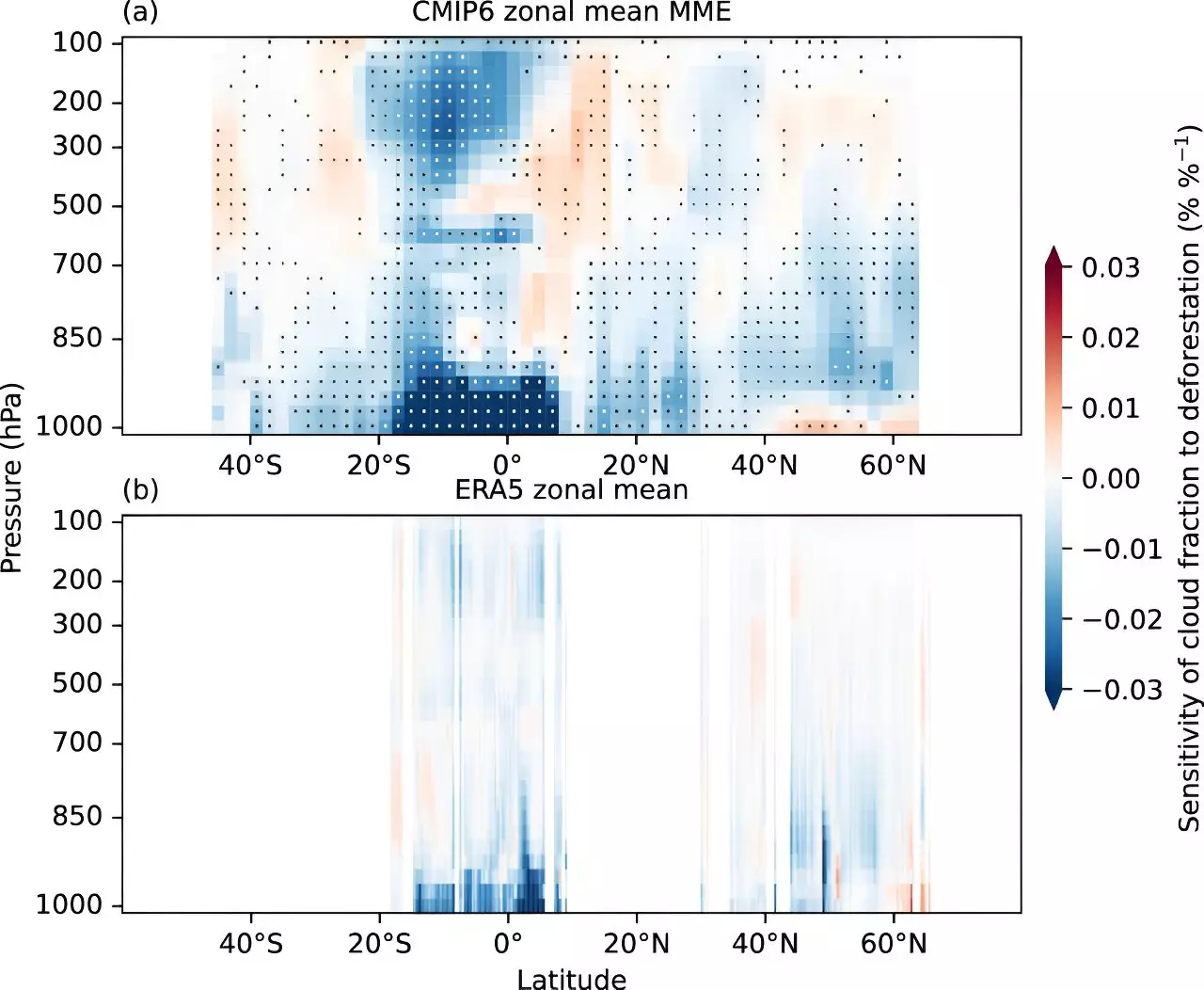

The work of Dr. Hao Luo and his colleagues sheds light on how large-scale deforestation alters cloud composition. With fewer low-level clouds present, the Earth is exposed to more sunlight, further exacerbating heating effects. As Professor Johannes Quaas explains, these clouds act as a barrier, reflecting sunlight back into space and moderating the planet’s temperature. The stark contrast between cloud behavior in forested versus deforested landscapes presents a new angle to approach climate change mitigation strategies.

This groundbreaking study employed advanced climate models and idealized deforestation simulations, providing a clearer picture of how the meteorological landscape shifts in response to extensive tree removal. The researchers carefully analyzed these simulations to link decreased cloud cover with identifiable meteorological changes, such as alterations in surface turbulent heat flux. These changes lead to a decline in uplifting currents and atmospheric moisture, both essential for cloud formation.

The implications of these findings are vast and resonate beyond the scope of meteorology. The researchers highlighted the critical need for interdisciplinary studies to unravel the intricate relationships between biodiversity, forest ecosystems, and cloud formation. Understanding these links is imperative in crafting effective policies for biodiversity conservation and climate change mitigation.

This research prompts a reevaluation of priorities in climate science. The current inquiry into the role of forest biodiversity—the variety of life within forest ecosystems—indicates that preserving diverse forest systems may also safeguard cloud cover and, by extension, our climate. The environmental community must focus not just on halting deforestation but also on restoring and protecting areas with rich biodiversity to reinforce their cloud-regulating functions.

As the understanding of these interactions evolves, it becomes increasingly crucial to integrate knowledge from various scientific fields. The work published in Nature Communications serves as a wake-up call, urging policymakers, scientists, and conservationists alike to consider how forest health intertwines with global climate stability. Harnessing this knowledge could be key to addressing the monumental challenge of climate change and safeguarding our planet’s future.

Leave a Reply